The Unbroken Spiral: Violence, Colonialism, and the Path to Peace in West Asia

As peace educators, we often speak of the cycle of violence. There are prejudices between two groups, maybe even ancient prejudices, leading to an atmosphere of distrust. This leads to some kind of act of violence, perceived to be motivated by racial hatred that then leads to a response. The response often takes the form of an escalation - “you” kill one person; “we” respond by killing 10. Escalation on one side leads to escalation on the other side and things get out of control. The spiral only ends when reasonable people sit down at the negotiating table and try to a) hold those who committed violence accountable for their crimes and b) take steps to address the underlying distrust and hatred and bring the two communities closer together.

I’ve been contemplating the cycle of violence and its implications in West Asia this week. As we learn of the extrajudicial assassination of Hassan Nasrallah, an act of violence that is being cheered in the mainstream press (just as they cheered the killing of dozens and the maiming of thousands in the pager and walkie-talkie violence of a couple of weeks ago) what can the “cycle of violence” theory teach us about this moment?

I think the first lesson is that without accountability, without at least an apology, things just keep getting worse. The original act of violence in historic Palestine happened nearly 100 years ago, when the avowed antisemite Arthur Balfour convinced colonial Britain to align with the settler colonial project we now know as Israel, thereby giving much of historic Palestine to Europeans and taking the right to live in Palestine away from the people of West Asia. That led to something Palestinians refer to as the Nakba, the displacing of some 750,000 people and the murder of some 15,000 people, by the forces that would then go on to form what is today the state of Israel.

When I was younger, many people believed that the cycle of violence was at an end. The Oslo peace process, which promised a two state solution with a state of Palestine to be established in the West Bank and in the Gaza strip with its capital in East Jerusalem, seemed to offer a way out. But for me it was always a partial way out without any accountability and keeping those who committed the violence in control of the process. Critics like the late Edward Said saw Oslo as capitulation, as surrender. By now this is not even a relevant discussion. Israel immediately started violating the terms of the Oslo agreement almost as soon as it was signed. This year the Israeli Knesset has voted that Israel can take over the West Bank in its entirety. Lack of accountability is not the only reason that Oslo failed, but it is a key reason.

An even deeper lesson of the “cycle of violence” theory is that there is a pattern of a particular form of violence going back more than 500 years. Back in the year 1095 of the common era (CE) the Vatican declared any land without Christians living on it to be “terra nullius”, meaning “empty lands”. These papal bulls were restated in 1454 and 1493 CE, soon after Europeans found a safe passage to the Caribbean. They were only formally renounced in 2023. When Europeans colonized Palestine in the 20th century they were still working under a racialised framework – those who aren’t European aren’t really human. (Here it may be worth remembering that although the Israel project is framed as providing a homeland for Jews, Zionism was originally a Christian project and even today the number of Christian Zionists vastly outweighs the number of Jewish Zionists.) And indeed terra nullius is affirmed by a saying that the Zionists made popular, but they must always have known to be a lie: “A land without people for a people without land.” (This saying has its origins in Christian Zionism in Scotland.)

The percentage of the world’s population willing to defend the Nakba, the Balfour Declaration or the Doctrine of Terra Nullius is, I believe, smaller today than it has been in centuries. But it is not yet zero. And the few who remain hold a lot of power and a veto over the UN Security Council.

In order to believe that these policies are justified, one must believe that the victims of these policies are somehow subhuman. And that dehumanisation is ultimately what keeps the cycle of violence going. If “your side” hasn’t really committed a crime because the people you killed weren’t really people, you’re never going to agree to be held accountable. If “their side” aren’t even human, you’re never going to agree to sit down at the negotiating table with them.

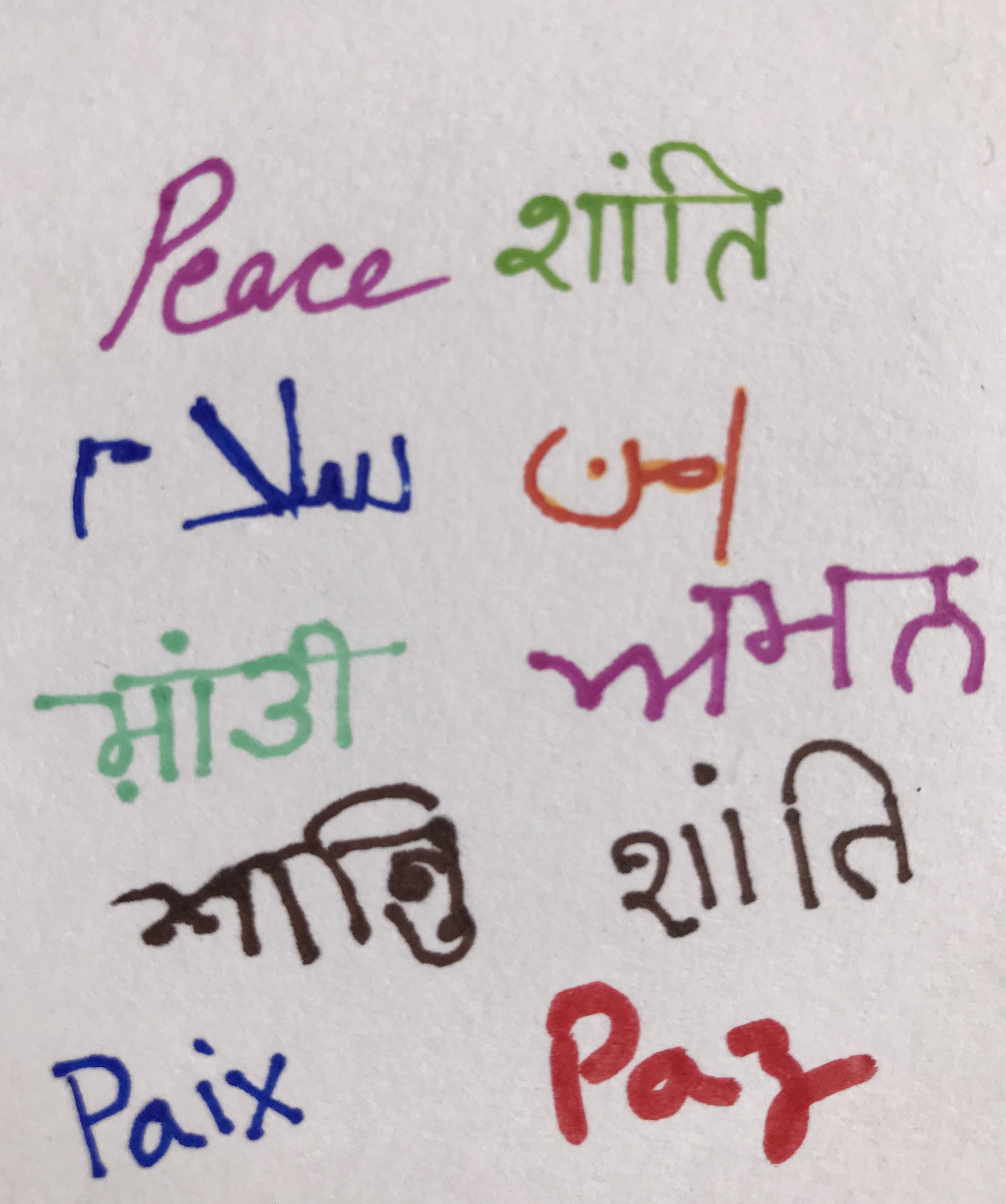

Peace depends on recognising that we are all human, with the same rights and the same aspirations. At the start of what would eventually become known as the US War of Independence, Patrick Henry said “Give me liberty or give me death.” Are these words the specific articulation of a person living in the 18th century whose desire for freedom outweighed his love of life? Or do they represent a universal part of the human condition? We all want power over our own lives and many of us would prefer death to any form of slavery or subservience.

As I write these words, there are Israeli bombs falling on Beirut, on Gaza on Yemen and on the West Bank. These bombs can and do snuff out innocent human life, but they will never snuff out the human desire to be free.

The last lesson that the cycle of violence offers is that violence rarely if ever stops violence. The only way to end the violence is through negotiations. If you commit acts of aggression that are brutal enough, you can delay negotiations, sometimes for a long time. In the 1950s and 60s, France was only able to delay Algerian independence by a few years when it killed as many as a million people in their effort to fight against what they then called terrorism and what we all now agree to be a struggle for the liberation of a colonised people. Israel is doing the exact same thing, even going to the length of killing the people with whom they were negotiating a cease fire agreement.

However long the stalling tactics last, the cycle of violence ends at the negotiating table, not on the battlefield.